Content Hangover No. 1 by: Garrett Crusan

The Simple Joy of Happenstance With Ryan Davis and the Roadhouse Band

(Union Pool: 12.05.25 // 12.06.25)

When God threw me a bone and granted me permission to see Ryan Davis and his ramshackle crew of alt-country misfits’ three sold-out shows at Brooklyn’s Union Pool, I neglected to show up with a notebook even though I intended to. I instead wielded a knock-off BlackBerry and a camera that I was too shy to use more than a few times at the matinee, which is not an arsenal fit for someone doing a writeup. I arrived two hours early with several others to the Friday night performance and waited patiently over a half-dozen smokes. Once I was let inside and surveyed the scene, the clientele spanned generations: patchwork-tattoo-sleeved half-baked indie Brooklynites, somebody’s grandfather, somebody’s grandmother, somebody’s father, somebody’s mother. Poets, musicians, college football fans. If I had a round of liquor every time I heard someone mention Cameron Winter, I would’ve been at Langone and hooked up to an IV-drip long before the first act went on stage. Read more about the three incredible supporting acts for these shows here.

While 2023’s Dancing on the Edge put Davis on the map as a new kind of Callahan-school writer with a knack for long-form, through-composed Americana odysseys drenched in a space-age world of synthesizers and drum machines, it wasn’t until this year’s masterful New Threats From the Soul that Davis dove headfirst into the semi-mainstream of this “genre revival” (if you’re the kind of person to consider acts like MJ Lenderman “mainstream,” or the kind of person to say “genre revival”). To say Davis had a “breakthrough moment”, however, is a radical understatement for what he and his ensemble are experiencing right now while embarking on the New Threats tour. He and his Louisville contemporaries have been at this for decades—his pages-long resumé includes the founding of Louisville DIY label Sophomore Lounge eighteen years ago, ego-dissolving avant-garde peregrinations with his Roadhouse buddies in Equipment Pointed Ankh, and a past four-record stint as a slightly gruffer, more rough-and-tumble country-punk frontman in State Champion—so you could say that he has “broken through” several times in his lifetime. Instead of “breakthrough moment,” maybe we should call it a “fucking finally” moment.

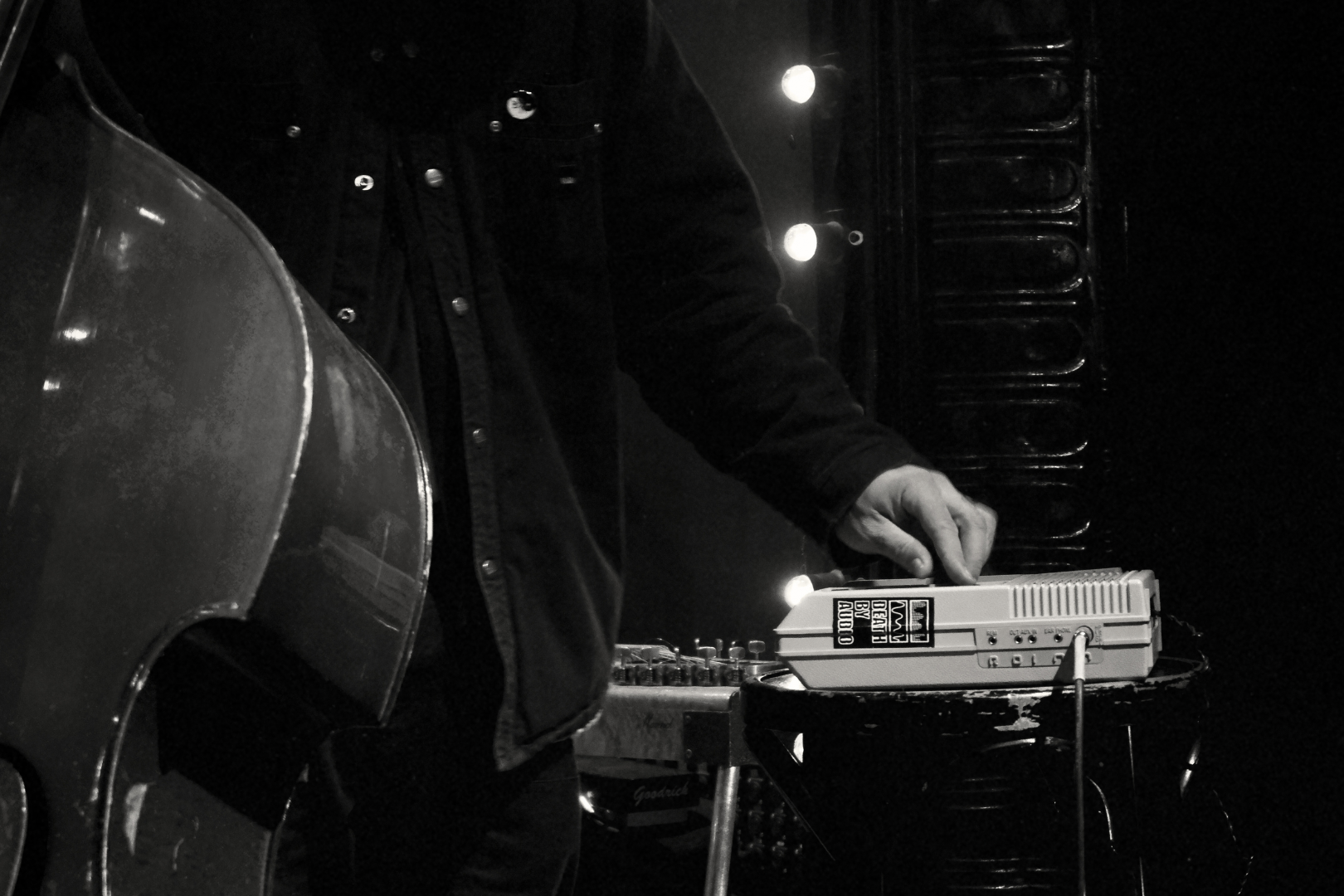

On Friday, the “fucking finally” moment was practically onstage with Ryan the Roadhouse Band, a tender but aggressive eight-piece machine on the brink of bursting into flames, all crammed onto Union Pool’s two-foot-tall, hilariously narrow and inconveniently shallow bandstand. The fragility of “fucking finally,” the opposition between the constriction of the band and their expanse of instrumental armaments, even the relative possibility of the breakdown of this musical mechanism suspended the audience in midair as the Roadhouse Band jumped right into the title track of New Threats. It sucked all of the air out of the room. They needed it more than we did, and we willingly surrendered it to them.

Start to finish, subtle improvisation was the name of the game. The pure electricity between every member of this cosmic-Americana orchestra was flooring; no one was making an attempt to replicate the performances present on either of Davis’s two projects, but rather augment and intensify them. Quieter cuts like “Junk Drawer Heart” became raucous, celebratory rock and roll—the drum machines and near-whispered vocals in the first moments of its recorded version were replaced with a two-minute-long sonic blast to set the track in motion. Davis’s delivery was executed with a lived-in Southern swagger that rivals even the golden age of the greatest country singers, and the Roadhouse Band were listening and responding to each other in a way that most bands would only dream of: not only with musical statements, but with facial expressions, laughs, dances that were real and not choreographed, glances that looked like references to inside jokes. We kept cheering after the show was finished, begging to not have the suspension ripped away from us, to keep holding our breath. The band didn’t even leave the stage; it was too cramped already. Davis joked, “Where would we even go?”

During “Bluebirds Revisited”, a song that Davis admitted was “literally the only other song [they knew] as a band” when cued for a second encore, he dissolved from his frontman-form and rematerialized as a guilty priest trapped in his own confessional booth:

“I don’t want to make death-rock anymore, I want to go to where my alarm clock won’t dare to come find me [...] where the sun don’t set, it rises twice and happy hours are subject to market price.”

The audience joined him in one last hymn before the night concluded: “These are instructions for disposal of my dick, as compared to my mind.” In that moment, despite any differences between all of us, 200 people became the same person. Crying, laughing, dehydrated—all able to breathe again. Accidental spills on a beer-soaked floor and a mutual, urgent passion were able to level the playing field between grandfathers and the young people trying to dress like them.

Ryan Davis’s opener, Silk FenceSaturday reared its head with a hangover. I was nearly late to the matinee. By the grace of God, I was able to make it despite the hot flashes. It was a different set with an even more amplified sense of electricity and celebration, maybe the most of all three I was able to witness. Maybe it was the Mobb Deep shirt that Davis adorned. I’ve never seen so many cups of coffee at a show before.

The Saturday evening crowd was ready to assert themselves as a choir more than any other night. “Free from the guillotine of doubt” never felt so good to belt out with misty eyes surrounded by a collection of equally misty-eyed people. We were all freeing ourselves from one thing or another.

Cigarettes don’t do much for you, but they do make you friends, odd ones sometimes, often in odd places. After the show, I was asked for one by a man named Stephen on behalf of his wife, Natalie. It was her birthday; therefore, it wasn’t the kind of question you can say no to, despite how little you may have left. I didn’t mind. I never do. We celebrated the birthday and performance together, and then Stephen made eyes at my copy of Dancing on the Edge. He mentioned that he had released that record in London, and we stumbled into a long chat. We agreed that acts like Davis might only come around once every twenty years or so, and he complimented my sharing of that sentiment, along with my knock-off phone. “Old school. Real.” He mentioned that the last time he felt this way about music was during his teen years in the era of Silver Jews (whose frontman, David Berman, shared an equally wordy, slacker-poet mentality to Davis and is often cited in the first paragraphs of any major publication writing about the Roadhouse Band) and the release of The Natural Bridge. We agreed that that was their best record. Another thing that he liked about me, he said. He called me “real” again, and he mentioned that I made him feel hopeful for the current generation of young music listeners; he, however, made me feel unique for taste that I thought was textbook. We stopped talking about music and moved on to our origins: a time he got mugged in London; his hometown of Coventry, where “all there is to do is get high and think about leaving Coventry.” He told me about someone reaching into his pants pocket in an attempt to steal a phone once, “Maybe it was a BlackBerry.” “Let’s go find Ryan.” I was too dazed at this point to imagine introducing myself to Davis, let alone articulate myself with any semblance of grace . I was just a kid suffocated by their winter coat, carrying around the guy’s record, somehow next to the other guy who took a chance on releasing it overseas: pure happenstance.

I shook hands with Ryan after he gave Stephen a long hug. He shook hands with a Tecate as well. He was smiling earnestly. It seemed like he genuinely wanted to be there; no looking over shoulders to see if there was anyone else more interesting to talk to, which was refreshing compared to other artists I’ve had the opportunity to meet in my time. I stood there half-drunk, taken aback by how normal this guy was. I had to fight the urge to piss for a lot of the show prior to this, because there was no way of weaseling out of the standing room. I really had to piss when I got to talking to Ryan because I hadn’t in hours. I could feel myself looking like I was going to piss myself.

I thought then that maybe I’m not a “real” music journalist, because the only question I could really get in edgewise was, “What are you reading?” I could’ve asked him any question in the world, and that was it. “What are you reading?”

A great answer: “I’m in the middle of a few things right now,” to start. He went on: most memorably, a collection of short stories by Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, gifted to him by Will Oldham (better known as Bonnie “Prince” Billy). “The kind of book you need to take breaks from reading.” My favorites, I said. I mentioned my love for Lispector, but I kicked myself for realizing after the fact that I had only read Hour of the Star for a class at NYU, not on my own volition. I do remember Lispector’s work impacting me regardless, just enough to throw it into conversation with any hint of confidence. Others mentioned were Gordon Lish and Atticus Lish, the latter Davis said was “actually probably asleep a couple miles from here right now.” Lists of books. Other authors were mentioned, and this is why I thought I might not be a “real” music journalist: I don’t remember some of them. I didn’t want to have a phone in my hand the whole time because it wasn’t an interview; it was too slow to type on anyway, and I had a record in my hand so I couldn’t take notes even if I wanted to. I could give hundreds of excuses. While Davis was at once a formidable force in my head, he did, thankfully, turn out to be the easiest person in the world to not be a “real” music journalist around. All I really needed was one question, anyway.

It was getting late, and I didn’t want to overstay my welcome. Stephen kept telling Ryan what he had told me before, “This kid is for real, this kid is the real deal, etc. etc.” I couldn’t help but feel embarrassed when he mentioned that; I’m definitely not the only 20-something in Brooklyn who thinks The Natural Bridge is the best Silver Jews record, definitely not the only one who sticks around after shows and hopes for some kind of beautiful happenstance to come “howling down from the side of a mountain somewhere,” and definitely not the only one who feels an overwhelming sense of urgency to seek out the religious experience of live music. I think I know a few of those people. Maybe that means that we’re all the real deal.

I tried my best to recall the night from start to finish. I gave an honest attempt at putting the pieces together by writing notes on my phone while walking back to the train. That was a mammoth task that proved to be near-impossible: Ryan Davis and the Roadhouse Band were expertly executing a special kind of magic at those shows with grace and style, and if you aren’t the magician, maybe there’s little point in wasting your time trying to explain the trick.

Ryan Davis’s opener, Silk FenceFor all inquires or possible coverage please email chewgumonline@gmail.com